Collaborating for a Hunger Free Alexandria

March 10, 2020

According

to Feeding America’s Map

the Meal Gap

there are over 860,000 Virginians who are food insecure. The US Department of

Agriculture’s Economic Research Service defines food insecurity as a lack of

consistent access to enough food for a healthy, active life.

In

the City of Alexandria, one in five Alexandrians face food hardship. Food

hardship is defined as irregular access to affordable, healthy meals. Children

are disproportionately affected. At 15%, Alexandria has the highest child

poverty rate in Northern Virginia and 61% of children in Alexandria Public

Schools are eligible for free or reduced-price meals. This snapshot

demonstrates that hunger is a health and social justice issue that needs

addressing in Alexandria and the rest of the Commonwealth. As a state, we

will be unable to reach our goals for economic prosperity if all members of the

Commonwealth cannot reach their full health potential due to hunger and food

insecurity.

Food insecurity

negatively impacts physical and mental health. It can lead to numerous health problems

and have a significant impact on the short and long-term development of

children. For example, food insecure children are more likely to struggle in

school and other social settings. Food insecurity can also lead to or heighten

the severity of high blood pressure, heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and

obesity. Food insecure households are more likely to have higher healthcare

costs, or refrain from seeking the care they need due to financial reasons.

This perpetuates the cycles of poverty, food insecurity, and negative health

outcomes.

The

Action Plan for a

Healthy Virginia

challenges communities across the Commonwealth to actively lead and advocate for healthy

communities. At Hunger Free

Alexandria (HFA),

we believe that the most important part of what we do is bringing people

together to discuss hunger and food equity in Alexandria.

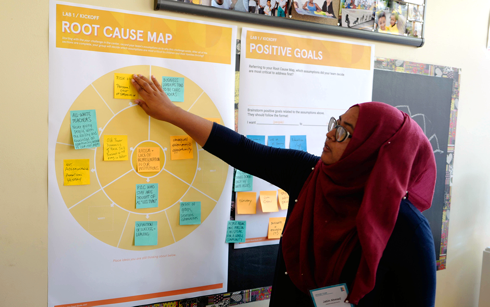

HFA

is a community-based coalition of

more than 20 food providers, faith-based communities, schools, social service

organizations, and advocates for ending hunger. HFA was created to address the

issue of food access and in doing so build a stronger Alexandria, which was

identified as an important need in the Partnership for a Healthier Alexandria

2014 analysis and report on hunger, “Toward

an End to Hunger in Alexandria,” that examined the emergency food system,

access to and utilization of government food assistance programs, and the role

of the private sector in food access within Alexandria.

HFA’s

mission is to coordinate community efforts to raise awareness of food

insecurity and to increase reliable access to nutritious, culturally

appropriate food in Alexandria. We convene our partners bi-monthly to discuss

needs, gaps, and redundancies. Hunger is a complex social justice and public

health issue. In order to address hunger, people and organizations from all

sectors must collaborate, so the diversity of our partners’ backgrounds and

areas of expertise is crucial. For example, one organization does not have the

capacity to eradicate hunger alone, just as one organization does not

understand or represent all the unique communities that live within the City of

Alexandria.

Together,

we are working to implement the Action Plan for a Healthy Virginia by:

- serving

as a hub for collection and dissemination of resources and updates and

distributes City of

Alexandria Food Assistance Resource Schedule.

- raising awareness

about hunger in the city by planning activities for World Hunger Day (October

16th–which we have rebranded as Alexandria Food Day). On Alexandria Food Day

2019 we collected over 6,000 pounds of food and hosted a community discussion

focusing on food equity in Alexandria.

- advocating to the city government for policy

changes and initiatives to help address hunger and food insecurity. For

example, in 2019, HFA advocated for the establishment of an Alexandria City

Food Warehouse, which is now food storage space for the largest food

distribution organization in the city, ALIVE!

- facilitating the

creation of new food assistance services, and raising and distributing grant

money through the Hunger Free fund.

Over the years, we have learned that

strong collaborations depend on new ideas and voices. HFA’s goals for 2020 are

to increase access to quality fresh produce and increase membership in

Alexandria. There is always room to expand and include new types of partners in

the fight against hunger, especially as we hope to include more voices of community

members directly impacted by food insecurity. Many organizations that serve or

distribute food to food insecure households called for the prioritization of

increasing access to produce. We heard them loud and clear and are currently

working on putting a strategic plan in place to accomplish this goal in 2020.

All

communities in the Commonwealth can benefit from identifying who is currently

involved in your food “landscape” (e.g. who is providing groceries or meals to

people, what retailers or farms donate food to these providers, who gleans at

farmers markets, your local government’s SNAP coordinator, etc.) and bringing

these players together to discuss successes, areas of improvement, and gaps in

service in the community. Partnerships can only expand from there, and no

willing voice should be excluded from the conversation.

The

power of bringing people together can never be undervalued, and HFA is hoping

to capitalize on collaboration in order to create a food secure city. We

encourage you to join us.

Ally Barbaro

AmeriCorps

VISTA

Hunger

Free Alexandria

Think about the last time you went to a

park. What did you do? What did you see? How did you feel on your way home? You

probably did some walking or exercise, saw faces both familiar and new, and

left feeling better in mind and body.

The Action Plan for a Healthy Virginia

encourages Virginians to engage in regular physical activity. Parks can be a

great location to support this goal, as well as multiple other health benefits.

Whether it be improved mental health; reduced social isolation and exclusion, chronic

disease, and obesity; or indirect benefits of reduced heat islands and

stormwater runoff (Gies 2006), parks are an invaluable community asset.

At the Trust for Public Land (TPL),

we believe that everyone deserves a park because of the individual and

community benefits described above. Similarly, we believe that health, as the

World Health Organization says, is a human right. And yet, like health, quality

parks are not equitably distributed in America.

Across the U.S., over 100 million

residents don’t have a park within a 10 minute walk. TPL, in partnership with

NRPA and ULI, leads the 10 Minute Walk Campaign

to get America’s mayors to commit to providing high-quality parks to all their

residents. Four cities in Virginia—Alexandria, Fairfax, Richmond, and

Roanoke—have signed onto the campaign.

Just living close to a park is shown to

reduce childhood obesity (Wolch 2011). To create a healthier Virginia its

critical that other local communities commit to increasing access to

parks.

But having access to a park is only the

beginning. The quality of parks matters too.

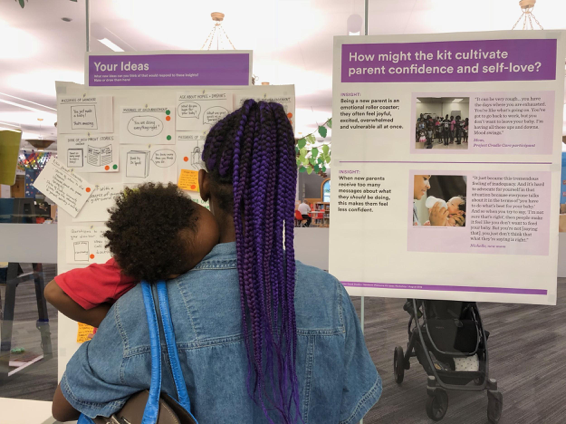

At TPL and in organizations across the

country, parks leaders are constantly seeking ways to ensure parks are an asset

to the community. Arts and culture can play a critical role in achieving this

goal. Whether it is using arts to communicate the needs of residents for a new

park or hosting a free performance celebrating identity and diversity in a

decades-old park, arts and culture is a valuable tool that everyone—even if you

don’t consider yourself an artist—can identify with.

Creative

Parks, Healthy Communities (CPHC), is an initiative of

TPL and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO),

to help health officials marry the benefits that arts and parks have on

community health. The benefits of place-based arts and culture are many and,

you may notice, similar to parks. They redress collective trauma, improve

social isolation and exclusion, address mental health, and reduce certain

chronic diseases (Sonke et. al. 2019). Greater than the sum of their parts,

though, arts and culture in parks and public space have the combined power to

sustain community capacity, social cohesion, and equitable community

development.

What does this all look like in action?

Take one example in Wenatchee, WA: Kiwanis-Methow Park.

The community surrounding this small and, until recently, blighted park is

predominantly Latino immigrants who, based on a health impact analysis, were

disproportionately experiencing mental health issues, lower civic

participation, and social isolation. Despite these challenges, spend a day in

Wenatchee and you’re left feeling inspired. There’s a sturdy and vibrant

cultural tissue connecting the Latino community that surrounds Kiwanis-Methow

Park. Mariachi groups, papel picado artists, and the best Mexcian food in the

state are all here and serve to promote regular contact with community members.

Given this abundance of arts and

culture in Wenatchee, TPL partnered with artists and community organizers to

engage community in ways that were familiar and could establish trust between

stakeholders, such as holding meetings at Mariachi Festivals and hosting a

“Health Wenatchee” festival where community members could visit the park and

receive free health resources, meanwhile providing rich and honest input on the

park project.

Through years of extensive engagement,

the results are remarkable and the park beautiful. There are 4,700 residents

who live within a 10 minute walk of a high quality park. Wenatchee residents

fought hard to fund a kiosko, or pavilion, in the heart of Kiwanis-Methow Park.

“The kiosko will be a place where the community gathers, a central point for

our pachangas (parties),” says Teresa Bendito, a young parks advocate who

co-founded the grassroots organization Parque Padrinos.

This capacity building around the park

has supported advocacy in other dimensions of community life. In 2018, The

Trust for Public Land and Parque Padrinos partnered with the Latino Community

Fund of Washington (LCF) to increase voter turnout in South Wenatchee. With

training and stipends from LCF, Padrinos knocked on 3,500 doors and made 4,200

phone calls to Latino voters in Wenatchee. When the ballots were tallied,

Latino voter turnout increased from 10 to 30 percent. Compared to the last two

midterm elections, voting by Latinos under the age of 35 increased by more than

200 percent!

As illustrated in the Kiwanis-Methow Park example, what starts as a park renovation can

become a social movement. When the process of creating public art engages

people in the neighborhood in a sensitive and genuine manner, it can be

profoundly transformative and improve the health of a community.

At TPL, we believe the most empowering

public art comes from envisioning by the community itself. There are invaluable

voices in your community that can shape not just how many parks are accessible,

but symbolize your community identity as resilient, creative, and healthy. So

the next time you are thinking about how to promote physical activity in your

community, consider how you might create better parks; parks that inspire and

engage.

You can learn more about your

municipalities parks on ParkServe.

Have more questions? Perhaps they are answered on Parkology?

Reach out to geneva.vest@tpl.org

for more.

Geneva Vest

Program Coordinator of Creative Placemaking

The Trust for Public Land

Works Cited

Gies, Erica. (2006). The Health

Benefits of Parks. The Trust for Public Land.

Sonke, J., Golden, T., Francois, S., Hand, J., Chandra, A., Clemmons, L., Fakunle, D., Jackson, M.R., Magsamen, S., Rubin, V., Sams, K., Springs, S. (2019). Creating Healthy Communities through Cross-Sector Collaboration [White paper]. University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine / ArtPlace America

Wolch, J., Jerrett, M., Reynolds, K., Mcconnell, R.,

Chang, R., Dahmann, N., … Berhane, K. (2011). Childhood obesity and proximity

to urban parks and recreational resources: A longitudinal cohort study. Health & Place, 17(1), 207–214. doi:

10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.10.001